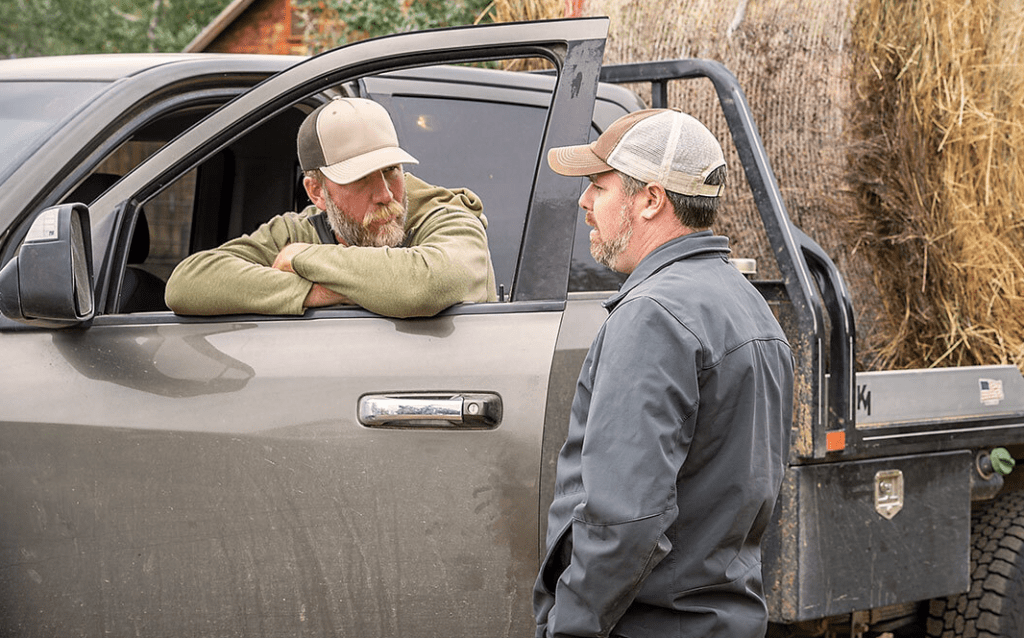

The method and technique of silage extraction is key to minimize the exposed surface.

Be safe, get the daily amount and leave a smooth face. These are the key factors when it comes to feeding out corn silage.

Silage is a conservation technique that relies on anaerobic fermentation to primarily convert plant carbs into acetic and lactic acid, and those acids will then preserve the rest of the material for future use. Because the ideal point of corn silage harvest is at black layer, by now (November) all silages would have almost sixty days since they were chopped and stored.

Most, if not all, producers are very aware of the importance of achieving the most tightness when packing the silage. All eyes are on the chopping and packing process that usually takes place in a short amount of time. In many cases, the process is performed by contracted crews, that specialize in the job, increasing even more the quality of it and attention to details. The situation could be quite different when the silo is open and fed out.

In a well packed silage, anaerobic fermentation would be complete in approximately three weeks, and from there on, if the silo is untouched, the material can be preserved for a long time. However, that state of long-term preservation will be negatively altered as soon as we start feeding the material.

Silages chopped at short particle lengths, with adequate compaction and little porosity, will guarantee swift anaerobic fermentation ensuring proper conservation, and will also help in reducing face spoilage once the silo is being used. That tight compaction (ideally, with densities of 15 Lbs. per cubic feet) will be achieved if we can balance dry matter content of the crop, chopping length, and a rate of delivery to silo that allows the material to be adequately packed in layers of half of a foot thick. So, what is desirable at the front, as we are making the silage, is for the same reasons, desirable during the time of silage feeding.

Once the silage is exposed to oxygen, aerobic fermentation starts to take place and the material starts to deteriorate. For that reason, it is recommended to minimize the silage face’s exposure to the air. Easier said than done.

Minimizing the silage face exposure to oxygen is key when feeding out, and it can be achieved in diverse ways, but it will depend on the way the silage was stored, the rate of daily use, the machinery available for the extraction and the skills and time available of the persons doing the job.

The method and technique of silage extraction is key to minimize the exposed surface. Having the right equipment for your needs is an obvious statement; however, you go to war with the army you have, and not the army you wish to have. Many times, particularly in small or medium size facilities, specific machinery to extract silage from storage, leaving a smooth face is limited or absent. If lack of specific machinery is the case, then operator skills become paramount. For instance, extracting silage from the silo pit, with a payloader results in a vastly different open face when the payloader is used going into the face from the front than when it is operated from side to side of the face “shaving” its surface. As a rule of thumb, 6 to 8 inches in depth should be removed daily from the entire face, which in many cases would be more than what is going to be consumed, forcing to use a section of the face.

In many cases, gear that has been specifically designed for the task is available, such as silage defacers, cutting frames, shear buckets, etc.

In the case that the operation lacks silage extraction specific gear, considerations to purchase gear include:

- Around 5% of material could be lost for aerobic fermentation.

- Feeding heated material can reduce cattle intake due to off flavors and odors.

- The number of heads that will be fed.

- How many days a year silage is fed and the equipment that will be used.

- The maintenance and depreciation of the equipment to be purchased.

- Issues and particularities of the operation, such as availability of labor.

A final and especially important consideration is worker safety when working with a silo vertical face that can collapse at any moment and without warning. This is particularly important when working in silo bunkers of large sizes, and heights.

In summary, remove the amount of silage that is going to be used, using the technique or gear that leaves the smoothest and smallest exposed surface possible, and be overly cautious when working close to the silo open face.

Source: UNL Beef, Pablo Loza, Nebraska Extension Beef Feedlot Specialist

Photo credit: Victoria Learreta Ruiz