President Trump has touted purchases of U.S. agricultural products as central to the trade negotiations with China. Photo: Daniel Acker/Bloomberg News

Some are skeptical that China can absorb the goods and that U.S. suppliers can deliver

By Josh Zumbrun and Anthony DeBarros

The Wall Street Journal

Updated Jan. 16, 2020 7:10 am ET

WASHINGTON—Call it the Big Buy.

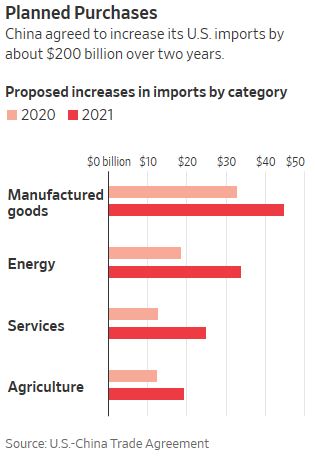

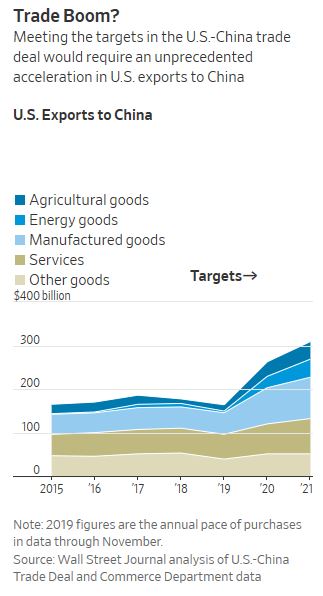

The U.S.-China trade deal lays out an aggressive schedule for ramping up China’s purchases of American farm products, manufactured goods, business services and oil and natural gas to levels never seen before—an increase of $200 billion over two years.

Can China absorb that much from the U.S., and if so can the U.S. deliver?

The two governments answer in the affirmative to both questions. But trade experts say the targets for 2020 and 2021 are so ambitious that they could stretch the capacity of even the world’s two largest economies.

What’s more, they say, achieving the targets would likely require significant government mandates put on China’s $14 trillion economy, which would be at odds with Washington’s support of market-driven business decisions.

“This is essentially the administration saying, ‘We’ve given up on saying we want you to become more market-oriented,’” said Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“The targets aren’t impossible since the Chinese control purchasing in most of the economy,” said Derek Scissors, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. But Mr. Scissors and others note that if the U.S. goods are simply diverted away from other countries and toward China, there could be little net benefit to the U.S. economy.

The text of the deal, signed Wednesday in Washington, spells out for the first time agreed-upon purchases across four broad categories: agriculture, energy, manufacturing and services. For each category, the increase ramps up in the second year of the deal, with U.S. exports to China nearly doubling by 2021.

U.S. trade agreements historically have focused on opening foreign markets to allow freer trade between businesses, not setting levels of trade on a government-to-government basis.

The deal specified targets for Chinese purchases, measured against 2017 levels. In 2020, China must buy at least $77 billion extra of U.S. goods and services, and in 2021 at least $123 billion extra, for a two-year addition of $200 billion.

In 2017, the U.S. exported $186 billion in goods and services to China, and the most recent data for 2019 puts the figure at about $160 billion. To meet the targets, exports to China would have to rise to around $262 billion in 2020 and $309 billion in 2021, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis. For this year, that amounts to an increase of around 60%, in what would be an unprecedented jump in bilateral trade.

The trade deal didn’t detail which categories of manufacturing were expected to provide the added sales. Negotiators have said there are specific targets but that they are being kept confidential to avoid distorting markets.

Trade groups said the signing was a positive step, but that further tariff reductions are needed on both sides before U.S. companies can expect to realize big gains in exports.

Trade groups said the signing was a positive step, but that further tariff reductions are needed on both sides before U.S. companies can expect to realize big gains in exports.

Dennis Slater, president of the Association of Equipment Manufacturers, said his group hopes the pact “will pave the way for the elimination of the remaining tariffs and increase U.S. exports to the Chinese market.”

Nathan Jeppson, chief executive of Northwest Hardwoods Inc., one of the largest U.S. producers of hardwood lumber, said his company isn’t forecasting a near-term increase in purchases by Chinese manufacturers of furniture and other wood products.

“It is very much cautious optimism,” Mr. Jeppson said. “We aren’t going to change anything about our production plans.”

The trade war has restrained commerce between the U.S. and China, but the value of goods exchanged is still up by more than 40% from levels in 2017, the year that serves as the baseline for the deal’s targets.

The biggest chunk of the $200 billion in increased purchases by China would come from U.S. manufacturers. The deal calls for manufacturing trade in 2020 to climb by $32.9 billion from the baseline level and be $44.8 billion above baseline in 2021.

President Trump has often touted the agricultural purchases in the deal as one of its centerpieces. To meet the goal for 2021, China would need to import a little over $40 billion in U.S. agricultural goods—a nearly 90% increase from 2017, according to the Journal’s calculations.

In addition to the purchase targets, China has agreed to steps that allow more market access for U.S. dairy products, poultry, beef, fish, rice and even pet food.

The aggressive targets met with skepticism from some farm groups. Michelle Erickson-Jones, a Montana wheat grower and spokeswoman for Farmers for Free Trade—a group that opposes tariffs—said that it remains to be seen whether the deal will deliver any meaningful relief “for farmers like me.”

“This deal does not end retaliatory tariffs on American farm exports, makes American farmers increasingly reliant on Chinese state-controlled purchases and doesn’t address the big structural changes the trade war was predicated on achieving,” she said.

Many grain traders said they would remain skeptical of the deal until purchases are actually reported.

“We want to see exact details by commodity and we want to see purchases,” said Rich Nelson, chief strategist at commodity brokerage Allendale Inc.

Despite the pledge of greater purchases from China, the most actively traded soybean futures contract on the Chicago Board of Trade finished Wednesday down 1.4% at about $9.29 a bushel, while corn fell 0.4% to about $3.87 a bushel.

While President Trump has touted agricultural purchases by the Chinese, the targets are even more aggressive in energy.

In 2017, the U.S. exported to China about $7.6 billion of the energy products specified in the deal. Meeting its goals would require energy exports of $26 billion in 2020 and over $41 billion in 2021. That figure represents more-than-quintupling energy exports, the Journal calculated.

American capacity to export energy, especially liquefied natural gas, has grown in recent years, but accommodating that volume could require a significant investment in energy infrastructure.

Beyond 2021, the U.S. and China said their deal envisions continued rapid escalation in purchases.

“The Parties project that the trajectory of increases in the amounts of manufactured goods, agricultural goods, energy products, and services purchased and imported into China from the United States will continue in calendar years 2022 through 2025,” according to the text of the deal.

—Austen Hufford and Kirk Maltais contributed to this article.

Write to Josh Zumbrun at Josh.Zumbrun@wsj.com